Ivy—Hedera helix

by Mark N. McCann

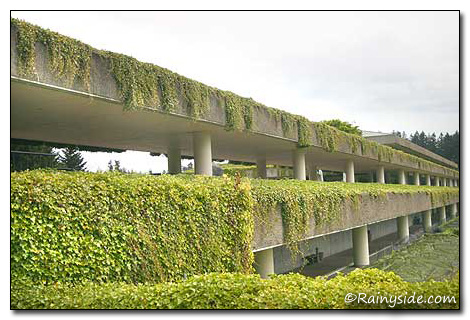

This species takes Rainy Side Gardeners out of the realm of gardening and into the arena of politics. The ongoing battle with English ivy, Hedera helix, has polarized two lobbies into opposing camps. No one wants to see "green deserts." Naturally, ivy will climb on or over what it can to seek out sunlight, smothering all plants in its wake. However, merchants seek to provide a product that some buyers request, a no maintenance, perennial ground cover. If those buyers could guarantee their ivy would not run rough shod through the surrounding countryside, no conflict would exist.

Not only does ivy reproduce vegetatively with tendril runners, and by pieces, but it also produces a dark berry that causes myriad distress in humans and, more importantly, in birds—diarrhea, loss of coordination, muscle weakness, et cetera. This insures winged agents will deliver the berries soon after ingestion. (Interestingly enough, two bird species can tolerate the ivy berries: European starlings, Sturnus vulgaris, and house finches, Carpodacus mexicanus—one is an introduced species and the other interbred with introduced similar species.) The rapid release of the berry assures that the seeds will be delivered in a environment similar to the mother plants. Hence we have the creeping green plague that covers our native forests and gardens.

Like so many of the invasive, non-native species we battle today, ivy was brought to this country long ago to remind early immigrants of the places that gave them the boot. Since those days, Americans have put as much distance between themselves and the European continent as possible, while remaining on planet earth. This pest would be better as nostalgia than the bane it has become.

Since this species has been listed as a noxious weed in the state of Oregon and a Class C noxious weed in Washington, it has been ostensibly illegal to sell commercially in some areas of the Northwest; however, some merchants have found a way around the law by selling subspecies or varietals of the Hedera. Conscientious gardeners go so far as to boycott these establishments that continue to sell species of the Hedera genera.

Additional hazards of the ivy are it harbors bacterial leaf scorch, Xylella fastidiosa, a pathogen that is harmful to many native plant species, and the dense cover provides a welcome hideaway for rats.

Identification

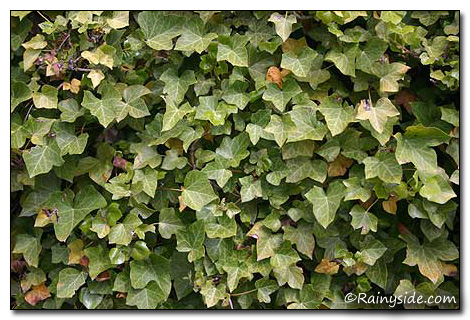

Most rainy side residents know what ivy looks like, but less seen is the mature (10 years +) round leaf form ivy takes on immediately prior to blooming. Under full sun, the small pale flowers will attract bees and flies in the early fall. The dark purple berries will hang on the vine through the winter, if not consumed.

Removal

Methods for removal cover every method from physical removal to voodoo. Regardless, follow up is the key. Ivy does have some small comfort to gardeners; once it is removed, many native plants may pop up in its stead, unlike English holly, which creates a wasteland in its shadow.

Removal of the vines from trees is not suggested; instead cut the vines, making sure to make a gap of at least a foot between the ends, and leave the tree-bound section to fall on its own. A healthy yank on a vine in a tree may bring down more than a gardener bargained for, so leave it. The root portion should be pulled up or dug out. Normally ivy roots do not run deep but may be extensive.

The tendrils can reach far and wide. The best method to collect them is the "tug and lug" method. Pull them up and put them in a pile to decay. Ivy stacked in a mound will rarely sprout anew, except along the edges. Small pieces left behind may still sprout, so repeated patrols may be needed to completely clear an area. If you must throw ivy away, please, put it in a "trash" bin rather than a compost bin.

Some areas of dense growth have been conquered with a rototiller. The deep tilling seems to break the roots, needing periodic spot checks to eliminate the pieces that may again take root. However, natives species probably won’t be seen as quickly as with the "tug and lug" method.

Suggestions have surfaced in regards to "walking stick" bugs, purported to dine exclusively on ivy, but why introduce a second species into the mix?

Last, and certainly least, are the herbicides. Triclopyrs and glyphosates can work but may need repeated applications. An attempt to incorporate hot water to reduce the waxy surface shedding of herbicides has shown some success.

Alternatives

Ferns: all ferns will do well in shady or damp areas, but the sword fern, Polystichum munitum, will also do surprisingly well in full sun.

Grasses: many species of Carex will thrive in the same spots as ivy.

Honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa): technically classified as a creeper rather than a climber, it can be trained to "creep" over most any surface. The orange trumpet shaped flowers will bring in an added bonus; humming birds love the showy flowers and sweet nectar.

Wild Ginger (Asarum caudatum): a wonderful creeping species from the rainy side. It will take some special care, growing best in conifer humus, and must be protected from slugs.

Wildlife Habitat

Because this species appeals primarily to introduced or crossbred native species, removing the ivy is best for all native species. Some butterfly and moth species do nibble on the leaves, but none so far have put a dent in the urban ivy population.

More reading: Trouble in Paradise—Invasive Plants

Mark N. McCann is currently working on a book about Green Space and Stream Stewardship within the Vancouver-Seattle-Portland-Eugene (VSPE) Corridor. Based on his five years of experience removing invasive species, and replanting and propagating natives species within the Tryon Creek State Natural Area (TCSNA) as a member of the Adopt-A-Plot program. He has been a Citizen Member of the Tryon Creek Watershed Council, Friends of Tryon Creek and presently is a volunteer at Berry Botanic Garden, specifically in the Native Plant’s Trail and in the Propagation Department.

Photographs by Debbie Teashon

Co-author Debbie Teashon's book is now available!

Gardening for the Homebrewer: Grow and Process Plants for Making Beer, Wine, Gruit, Cider, Perry, and More

Copyright Notice | Home | Search | Pest Watch